This summer Honors junior Haley Towne and senior Morgan Gaglianese-Woody, both biology majors, traveled for two-weeks with a faculty-led trip to Belize. Drs. Matt Estep, Sarah Marshburn, and Shea Tuberty all from Appalachian State University’s Department of Biology, led this trip. In this study abroad course, students earned six hours of biodiversity/ecology credits studying coral reef, rainforest ecology, and conservation. As Haley Towne explained,

Our focus was on studying the ecology and conservation efforts in the Belizean rainforest and coral reef systems.

Top photo features Morgan Gaglianese-Woody at Cox Lagoon holding a Morelet's crocodile. Photo by Dr. Shea Tuberty.

Photo above features the group at Tobacco Cay after they completed a trash clean-up. Photo by Dr. Matt Estep.

Morgan is working with Dr. Estep as her mentor for her Honors thesis. Of her experience in Belize, she shared,

Going with a class of eighteen other curious students and three inspiring professors put my experience into a perspective that would have been very different if I was just a plain ole tourist.

The main focus of the course was on the rich biodiversity of Belize. Gaglianese-Woody reflected,

Even before landing in Belize City, it became immediately obvious how beautiful Belize is. As we jumped from site to site, we saw flora and fauna that I had only ever seen in pictures. The rainbow of colors that blanketed the landscape spoke to its biodiversity. During each hike, walk, and swim, I was beyond distracted. I'd stop at every other plant or bug or fish and ask ‘What's this? What's that?’ I also couldn't help but wonder about the traditional context of what I was seeing. Could a certain plant be used as medicine, or a roof, or even as a needle and string? However, my experience was enriched by more than the flora and fauna. It was the discussions about conservation that truly sparked inspiration.

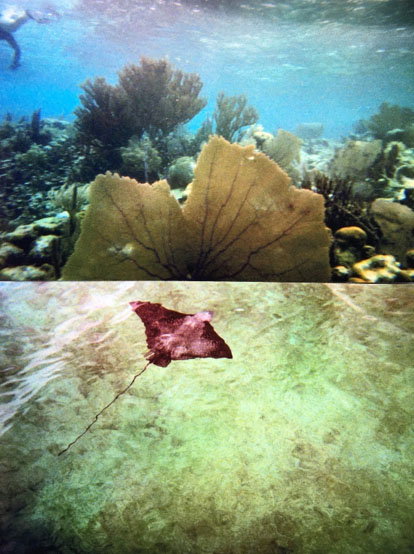

Photos above from Tobacco Cay show coral reef (top) and an Eagle Ray (bottom). Photo by Morgan Gaglianese-Woody.

Towne added,

Belize is a beautiful country with a rich history and stunning diversity. I have never seen more life in one square foot than I witnessed in the sea grass beds and coral structures. Nor will I ever forget how delicious fried plantains are after an all day hike uphill both ways in 100 degree weather.

Photo above features one of many delicious vegetarian breakfasts they enjoyed in Belize. Photo by Haley Towne.

Conservation was another area of focus of the course. As Towne furthered,

It was an incredible experience and truly opened my eyes about the complexities of conservation in a developing nation. For me, I think the lightbulb moment occurred during a lecture by Dr. Young, a scientist turned government official. He explained to us that in a nation so impoverished and hard to govern, ‘conservation is a luxury.’ The local people have relied on the land for their sustenance for generations and it is unreasonable to believe that they can be dissuaded from doing so when there is no alternative in place that guarantees their survival. As a biology major, and someone who has always had the option to place the wellbeing of the earth over that of the people, this changed my perspective in a big way. I will always carry the knowledge that conservation has to involve the conservation of local people to be successful as I continue to pursue biology.

Gaglianese-Woody described,

The complexities of conservation, social security, and ecotourism in Belize became apparent during our talks with Dr. Colin Young and Dr. Ed. It was during those talks that I sunk into myself a little bit, uncomfortable with my privilege. How can a country conserve the attractions of its economy without neglecting its citizens, 40% of whom are at or under the US$3,000 poverty line? During our class’ discussions, it became clear that there is no clear answer, and ensuring the social well-being of Belize requires a joint effort among its citizens, its government, and conservation organizations. But even after these crushing lessons, the compassion and optimism of the people teaching us inspired hope, which made me even more interested in a conservation career.

After considering the problems that trouble Belize, I began thinking about how our conservation lessons could be translated to conservation in the Blue Ridge Mountains. For example, how can scientists better inform a frustrated general public about the importance of conservation without boring them with political and scientific jargon? I can even consider these types of questions while executing my honors thesis project, which focuses on the conservation of Allium tricoccum, or wild ramps. More specifically, how can we inform population management practices without hindering the rich Appalachian traditions that rely on ramps? This question, just like all big picture questions, has no simple answer. However, as stated already, I do know that the answer involves the joint effort of communities, the government, and conservation organizations.

Another important lesson I gained from Belize was about the interconnections of the landscape. One of our assignments involved researching and presenting a community type that exists in Belize. During the presentations, the connections among community types were obvious. I began considering how the fate of one community influences the fate of other communities. For example, how does the loss of coral reefs affect the health of mangroves and sea grasses? Or how does the loss of riparian zones change the composition of the rivers that feed the coastal waters? Additionally, after picking up trash on Tobacco Cay, which was exceptionally difficult yet enlightening, I began thinking more about the interconnections among human activities and decisions. When I saw water-bottles from France and piles of bottle-caps that floated from some far-away land, I had no choice but to reconsider and question my lifestyle. Could I carry around Tupperware and a cloth handkerchief instead of purchasing paper plates and napkins? Or what if I just filled my reusable water-bottle instead of purchasing a plastic one? One thing's for certain, my individual footprint may be small, but a collection of 7.5 billion footprints is not.

Photo above Gaglianese-Woody holds a red rump tarantula Monkey Bay. Photo by Dr. Sarah Marshburn.

Photo above features a tapir, the national animal of Belize, at the Belize Zoo. Photo by Haley Towne.

Overall, these Honors students benefitted tremendously from this short-term, faculty-led, study abroad trip. For two Honors biology majors with concentrations in ecology this trip provided first-hand experience in a globally comparative context. The new perspectives they gained will impact how they approach their future work. They are now asking, as Gaglianese-Woody suggested,

So what can I do to act and teach accordingly?

Gaglianese-Woody performing a transect in the Broadleaf tropical rainforest outside of Rio Frio cave. Photo by Sarah Marshburn.

Photo of Belize from the plane when the group landed. Photo by Haley Towne.

Story by: Garrett Alexandrea McDowell, Ph.D.